Asymptotic Stories of Three Chants1

Once, a community devoted to spiritual practices and a contemplative way of life gathered here. They celebrated the world’s wonders with joyful chants, calling upon the sun, water, fire, wind, and a whole host of creatures and natural elements as brothers, sisters, and companions.2 They turned the walled enclosure into a school, and the surrounding grounds into orchards and gardens, from where they admired the ocean stretching out endlessly… Now, a different community inhabits these places — and their chants are different too.

First Chant3

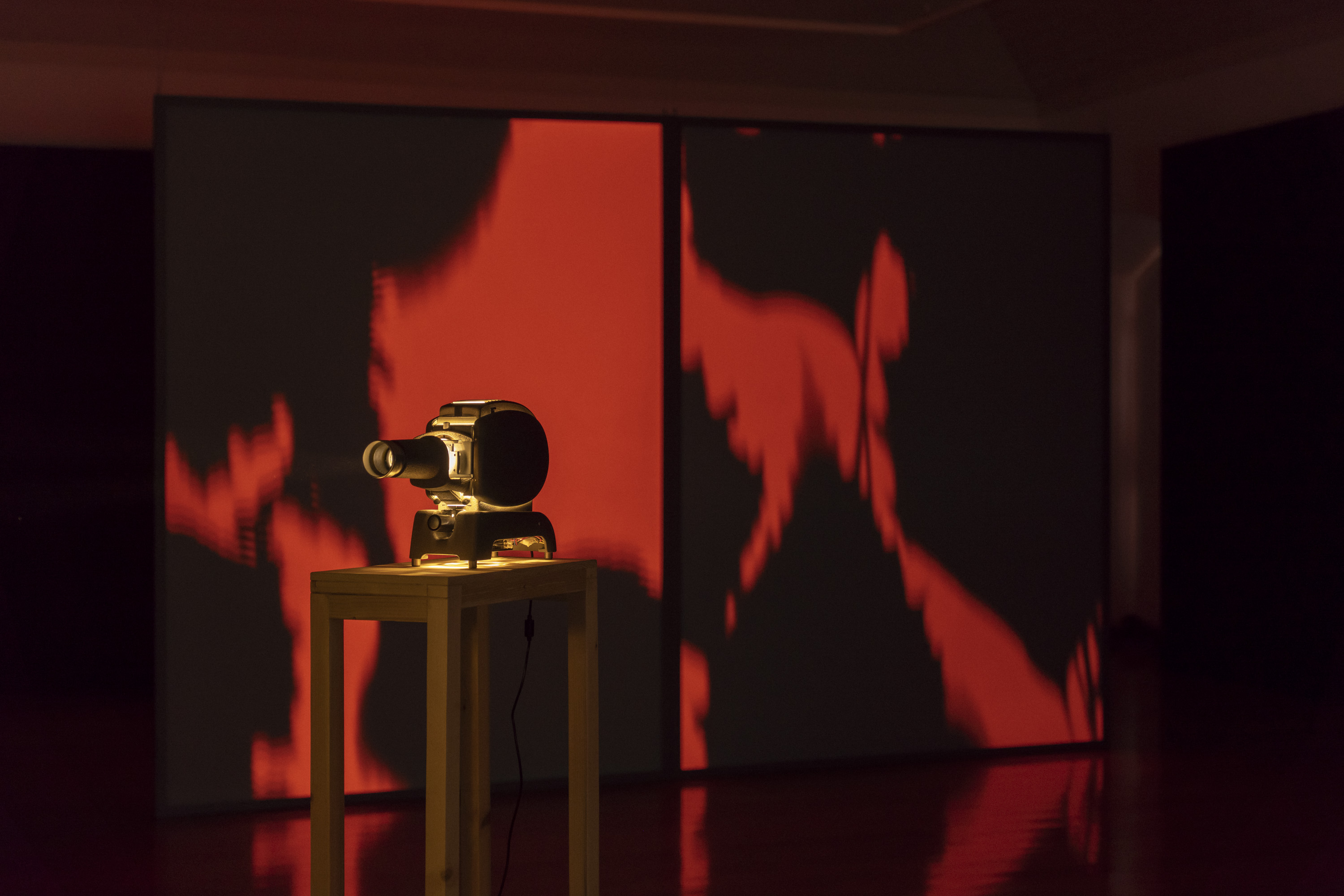

[or the Chant of the Bird]

What changed?

I can’t quite say. I still see the sea, and the cliff — abrupt, blood-hued, its earth laid bare by millennia of dryness — rarefied, imposing — from which I steal small twigs. But the trees are sparse now, and I no longer feel the flight in my body, for the wind has abandoned my wings. I thought I was flying, because I carried the dream within me — until, from the guttural mouth of a fish-dragon, I heard the howling laughter of other synthetic notes, and a metallic sound — a blow! pum — that echoed through the air with the stiffness of time. In that moment, I believed the dream had left me. And on my first attempt, I plummeted.4

It is said that that strange, two-legged creature [poor thing, it stumbled on them, tripping over its own self-invented superiority!], never having known flight in its body, tried to imitate the birds, and from its mouth escaped other kinds of notes.

The music swiftly freed the bodies from their inertia, from the materiality of their presence,5 granting them the seductive illusion of belonging to another world. The philosopher argued that colours ought to be reintroduced into music — which would necessarily entail establishing a system of correspondences between sounds and colours6 — for it is colour that renders the body present, even if at times in an ethereal and elusive form. Our formulation might follow yet another path, recalling the theory of substances proposed by one of the most renowned international members of that first community:7colour as a bodiless substance that only finds consubstantiation in a body. Music knows nothing of colour, yet it speaks its interstices.

Apparently, it was easier for the inventor of bird imitation to place his faith in another analogy — between his rudimentary babble and our winged song. Perhaps that’s why he came up with that idea — one that wouldn’t have occurred even to water (the first to know language in the world8) — that everything happens in the head, somewhere between the mouth and the ears, forgetting the body altogether.

He needed only to create a sounding box — like our marvellous lungs — to send his own guttural sounds back into his ears, in endless, interlaced anagrams. Still (un)satisfied, and rejecting time — that invisible force that seems to consume their bodies, preventing them from grasping music and flight in an eternal cycle — he made the clapper of a bell, hanging dead,9 their head.

(When we die, hearing is the last sense to fade)10

Second Chant11

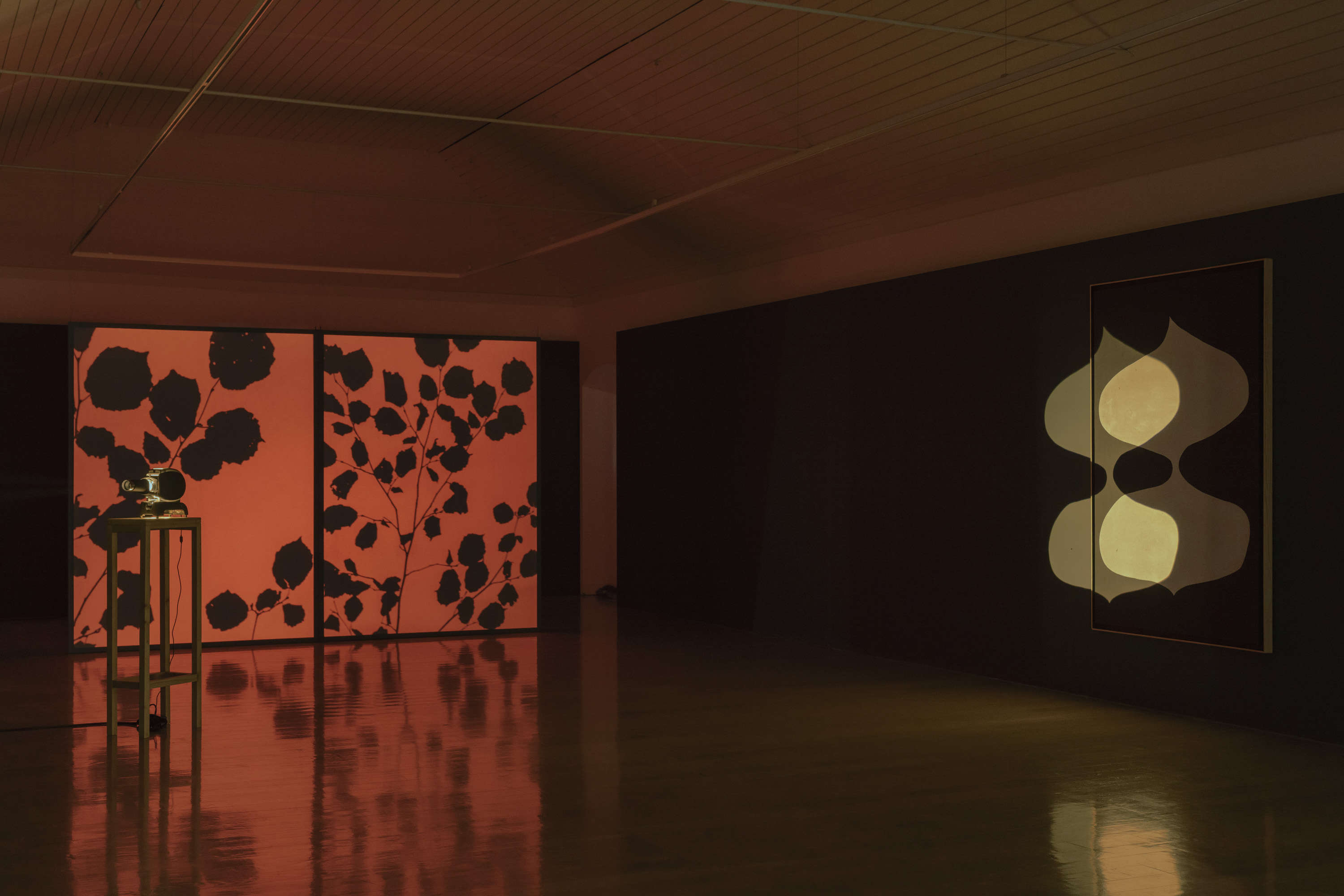

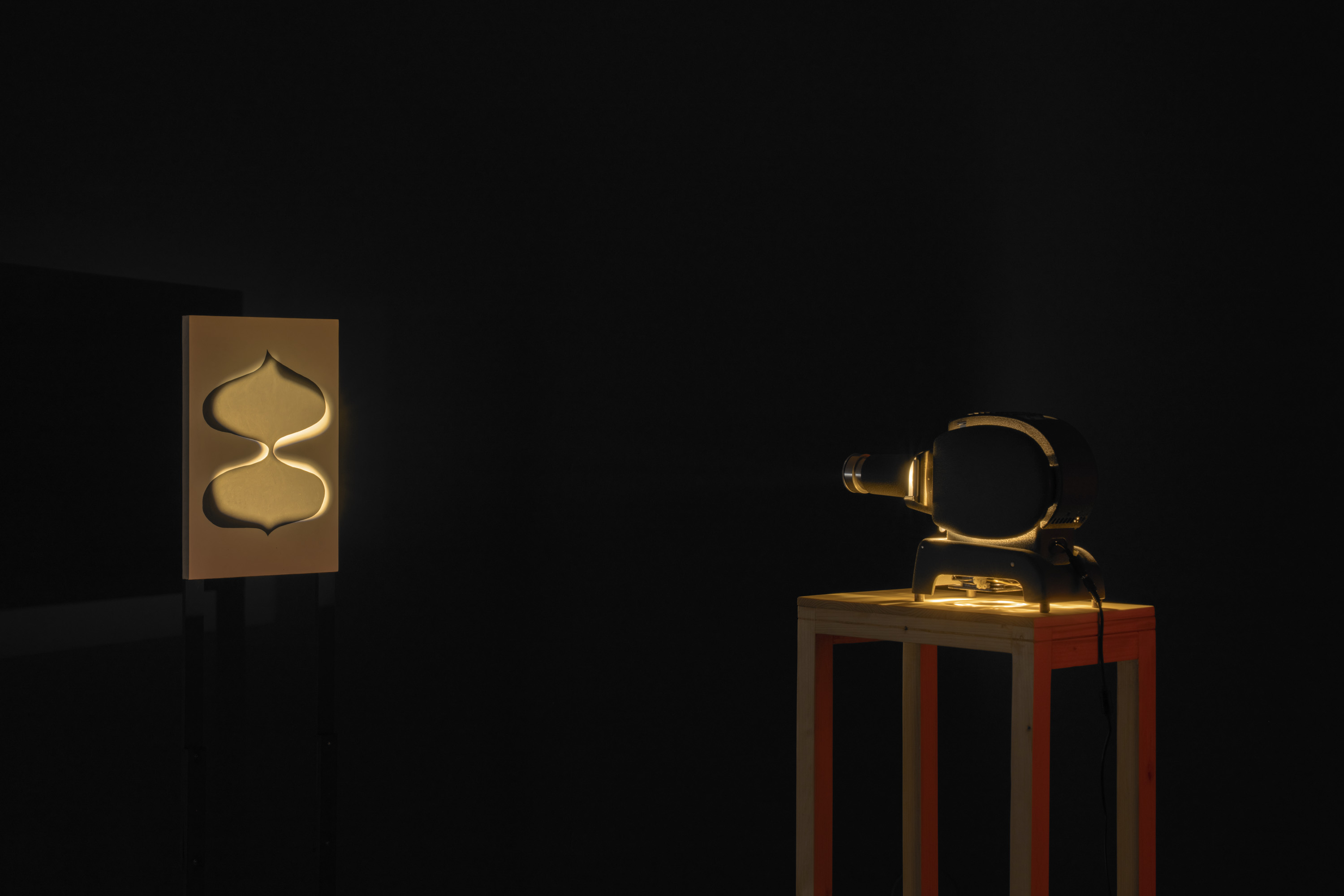

[or the Chant of Water]

What remains in my absence?

I never had a colour of my own, yet was always assigned shades of blue or green — hues imbued with an evocative or evanescent quality. In my absence, only bones and fossils remain, submerged in an acid-green sludge that corrodes everything, inflaming the gaze.

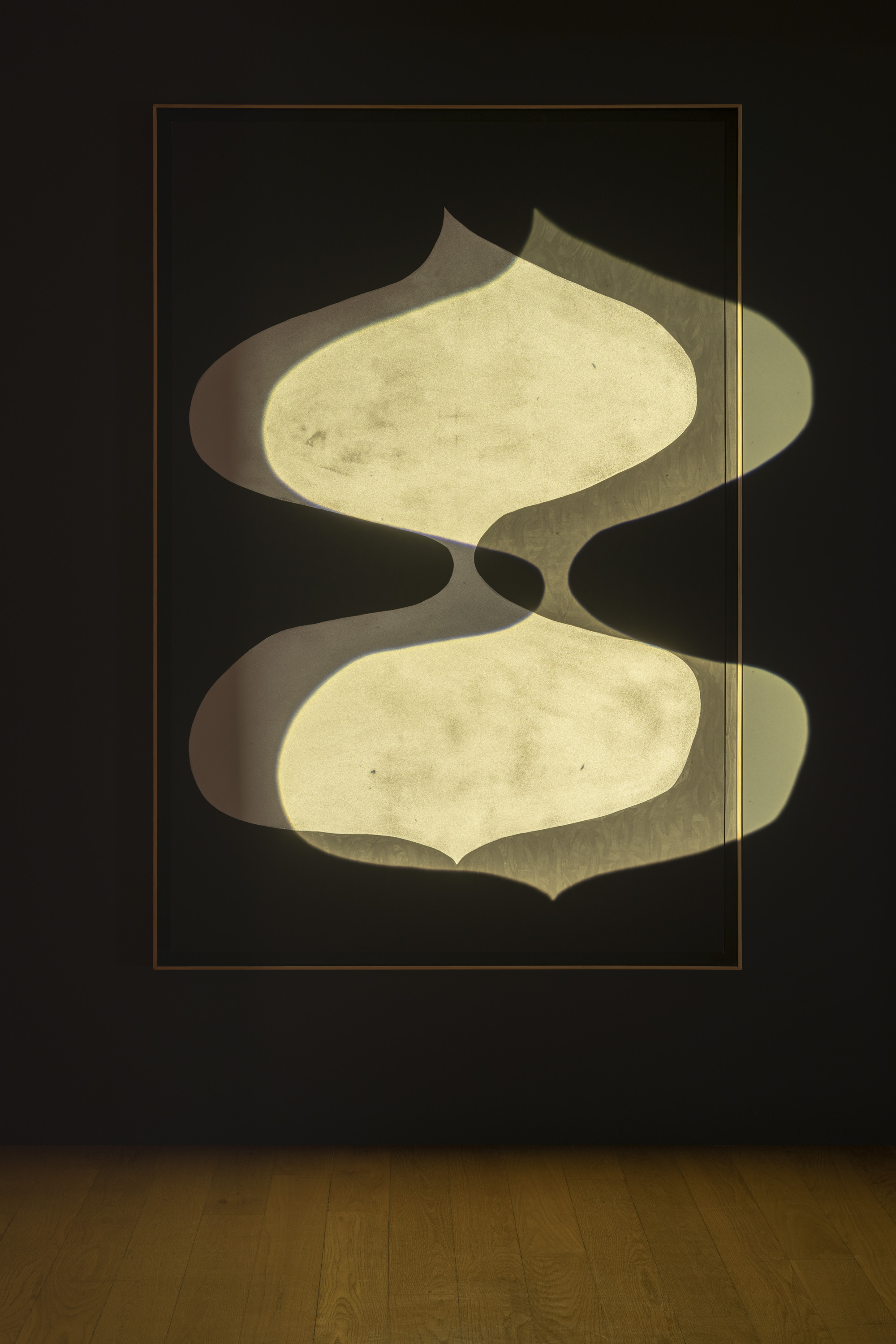

The hypnotic gaze becomes possible only in that intangible interval between revelation and disappearance. The green, burning eyes of the mythical creature12 had been replaced by painted optical discs which, reflecting on my surface — spinning, spinning — conjured the ghostly presence of its elusive body.

The colours return to primordial dust, staining all they touch. But there is no longer any sense of touch — only a mineral stillness rests on what remains: horn-shaped limbs of an unintelligible body, immersed in suspended time. The only forms that seem to endure — perhaps still harbouring a latent anima — point towards traces of that archaic language, shared with me by plants and animals: a proto-language of the living Earth, preceding words. Yet, [w]hen we see beauty in desolation it changes something inside you. Desolation tries to colonize you.13 Only desolation recognises and knows my absence.

In a cloak of dried mud, among skeletons of houses and factories, rotten branches and streets that no longer flow, my deepest scars crack open. Against the desolate landscape, the child’s body sketches a figure upside down. The legs seem to entwine, rehearsing a complex inversion, sketching the fragment of an imaginary circle — as if, through the child, the breath of the air that pervaded earlier days caress us14 as it recreates itself in a movement both of ending and beginning. If so, then there is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Then our coming was expected on earth. Then, like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak messianic power, a power on which the past has a claim. Such a claim cannot be settled cheaply.15

But the child takes it as a game. A game between figure and ground — a ground that melts away, a ground that loosens and releases the thread, drawing a circle; the circle then lets go and sketches yet another form, endlessly, again, each time anew. The upside-down world ignores this circular dance that sets in motion a time beyond the time each one awaits for themselves. My movement has ever been fluid and deeply circular, even when made a mirror or a translucent ground of colour, granting me a surface and depth both illusory and enchanting, from which emerge dark shadows — traces of other lives, of a burning nature — which, as they settle like pure, fluttering shadows, recall the dance of the child or that of Dionysus.

Third Chant16

[or the Chant of the Wind]

What do they flee from, in such haste?

From paradise, I always blow untimely.

The philosopher called me Progress — a reckless force that destroys all and leaves ruins behind. When divine power interferes in the earthly world, it breathes destruction. That is why nothing in this world is permanent.17

The Angel18 still gazes, rigid and motionless, his wings entangled in my currents, catastrophes piling up before his stunned eyes. How he would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But my breath is so strong, it has got caught in his wings that the angel can no longer close them. I drive him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky.19

The walled garden of Paradise20 was but a first deception — wrongly judged as a way to contain untimely forces and tame Mother Nature, when, in truth, it was meant to protect her from humanity’s voracious appetites. When Priapus — son of Dionysus and Aphrodite, god of fertility and nature, guardian of gardens and beasts — appeared, erect and monumental, submission was already underway.

But my breath — that never ceased — the endless breathing of a timeless time, crossing eras, bodies, myths, without direction, without destination (I delight in stirring whirlwinds). The garden no longer splits good from evil, nor the divine from the earthly, nor future from past; and guarding it stand two grotesques:21 Gargantua on one side, Pinocchio on the other, both beneath the face of Priapus, who bestowed upon them, in his own image, that crucial attribute of dominion (or is it survival?). Huge bodies roam the garden of metamorphoses, where beauty and grace dance with the scattered relics of the past, while I try out other paths.

From paradise I blow — and blow ever stronger…

Some are already fleeing, faltering, forgetting there’s no Angel to break their fall.

Susana Ventura

July 2025

Views of the exhibition Carma Invertido, by Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela. A Contemporânea project at Convento dos Capuchos, Caparica. Curated by Susana Ventura. Photos: Carbonara.st. Courtesy of the artists and Contemporânea.

Von Calhau!, A sina do sino pelo gargalo da gárgula, 2025. Traces of the performance/concert at Convento dos Capuchos, Caparica. Photos: Carbonara.st. Courtesy of the artists and Contemporânea.

Mattia Denisse, Agora Há Retiro Des-Cuidados, 2025. Mural painting at Convento dos Capuchos, Caparica. Photos: Carbonara.st. Courtesy of the artist and Contemporânea.

Opening

July 19, Saturday

17h-21h

Until

25.10.2025

Horário

Tuesday to Saturday:

10am–1pm / 2pm–6pm

Closed on Sundays, Mondays, and public holidays

Location

Convento dos Capuchos

Rua Lourenço Pires de Távora, 2825-041 Caparica, Almada

Organization

Contemporânea

Support

DGARTES

Câmara Municipal de Almada

Inverted Karma

Mariana Caló e Francisco Queimadela

Guest artists

Mattia Denisse e Von Calhau!

Curated by

Susana Ventura

Artistic Direction

Celina Brás

Executive Producer

Helena Mendoça

Design

Joana Machado

Photos

Carbonara.st

PT-EN translation

Susana Ventura

Acknowledgements

Alexandre Lemos, André Cepeda, António Baptista, António Cabanas, Sr. Belmiro, Sr. Cardoso, Dona São, Celina Brás, Cristina Grande, Sr. Eduardo, Filipa Oliveira, Francisca Bagulho, Helena Mendoça, Hélio Caló, Jaime Silvestre, João Alves, João Pais Filipe, Jolon, Jonathan Saldanha, José Augusto, José Vaz Bicho, Leonor Ventura, Lurdes Sá Lopes, Luzia Sousa, Manuel das Veigas, Manuel do Meimão, Margarida Alves, Maria Gabriela, Marta Baptista, Mattia Denisse, Nuno Aragão, Paulo Santos, Pedro Rocha, Pedro Sarmento, Ricardo Nicolau, Rui Castanho, Susana Ventura, Tó Zé da Quarta, Zarco Azevedo, Zé Maria

Entrance

Free

Room Sheet

Convento dos Capuchos / CMA

Susana Ventura (Coimbra, 1978) is an architect by training (darq-FCTUC, 2003) but prefers to dedicate herself to research, writing, and curating, exploring the intersections of architecture, art, and philosophy. She holds a PhD in Philosophy with a specialisation in Aesthetics, supervised by José Gil (FCSH-UNL, 2013), and is currently a Contracted Researcher at the Center for the Study of Architecture and Urbanism at the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Porto (CEAU-FAUP). She has served as an Invited Assistant Professor at Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Minho, and Évora. Among her various curated exhibitions are "Utopia/Dystopia" (with Pedro Gadanho and João Laia, MAAT, 2017), "The House of Democracy: Between Space and Power" (Casa da Arquitectura, 2018), "Radial body" (an exhibition by Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela, Municipal Galleries, Lisbon, 2020), and "The Tale" (an exhibition by Tiago Baptista, Rialto 6, Lisbon, 2022). In 2014, she received the Fernando Távora Prize (9th edition) and represented Portugal at the Venice Architecture Biennale in the same year. Since 2020, she has been the host of the radio program "Aforismos Espaciais" on Radio Antecâmara, dedicated to exploring the connections between architecture, literature, visual arts, poetry, and cinema.

- The Three Chants correspond to three Asymptotic Stories, a concept we appropriate from Mattia Denisse — “Asymptotic stories, like lines, run parallel and contaminate each other without ever merging” (Mattia Denisse and Arthur Dessine, Cata Log Cata Strofe. Lisbon: Dois Dias edições, Fundação Caixa Geral de Depósitos — Culturgest, p. 313) — to reinterpret the works of the different artists gathered in Carma Invertido: the duo Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela, the duo Von Calhau!, and Mattia Denisse (who at times also coexists with a double of himself). Without hierarchies and without blending into one another, their works trace parallel paths, yet belong to the same time and shared space. In the infinite, there is no promise of encounter; but within bodies persists the possibility of a collective inscription — small contractions, spasms, memories, or melodic landscapes.In this text, between the three Chants, common images erupt, fragments of bodies and resonances among fields of thought. They do repeat — yes — but always differently: perhaps the eternal return itself is a figure of inverted karma; neither one nor the other obeys a fixed direction, times intermingle — past and future entwine — and the sense of potency — the Yes as affirmation of life — even for Nietzsche, was never guaranteed (but as hypothesis, belongs to Dionysus).

- A distinctive feature of the Franciscan Order — to which the Convent of the Capuchos in Costa da Caparica, founded in 1558, belongs — is its reverence for nature. Saint Francis regarded animals and all forms of natural creation as brothers and sisters to humankind, as he celebrates in his poem Canticle of the Creatures.

- The first Chant offers a reinterpretation of the work by Von Calhau! — A sina do sino pelo gargalo da gárgula — conceived for the Chapel and Cloister of the Convent of the Capuchos, in Costa da Caparica, drawing upon two emblematic elements of the site: the bell and the gargoyles.

- During our visit to the Convent of the Capuchos, we discovered that black redstarts nest inside the gargoyles of the cloister.

- Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon — Lógica da Sensação. Lisboa: Orfeu Negro, p. 107.

- Deleuze, Francis Bacon, p. 109.

- We speak of John Duns Scotus, Franciscan philosopher and theologian.

- In this passage, we share an idea from David Abram, who suggests that language, for traditionally oral communities, is not an exclusively human trait, but rather a property of the animate earth in which humans partake (David Abram, Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Vintage Books, p. 11). We also assume that, in the very emergence of life, it was water that first came to know language.

- A church bell, usually suspended in a tower or belfry, is typically held in a static position — commonly referred to as being “hung dead.”

- Andreia C. Faria, Alegria para o fim do mundo. Porto: Porto Editora, 194. Translation by the author.

- The second Chant offers a re-reading of Inverted Karma, an installation by the artist duo Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela, bringing together works from different phases and media of their practice. These are newly reconfigured in light of a more recent body of work, now in close dialogue with the spaces of the convent.

- We are referring to the lynx from Edge Effect.

- Quote taken from the book Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer, used by the artist duo Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela in the introduction to their installation Analphabet Alphabet.

- Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Volume 4 1938-1940. Cambridge, London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University, p. 390.

- Idem, Ibidem. The quote, nonetheless, was made to yield to the enunciating voice of this Chant.

- The final Chant originates from the mural intervention by the French artist Mattia Denisse, entitled Agora Ha Retiro Des-cuidados. On a first visit to the site, the artist read Des-cuidados instead of Decuidados—the phrase inscribed above the entrance to the elevated garden. During the Martinho Depression (March 2025), part of it was destroyed.

- Benjamin, Selected Writings, p. 392.

- We refer to the celebrated passage by Walter Benjamin, which takes Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus as its allegory.

- Benjamin, Selected Writings, p. 392.

- Etymologically, paradise derives from the ancient Persian pairidaeza, meaning “walled enclosure” or “walled garden,” which was adopted into Greek as parádeisos, a term used to designate the Garden of Eden in the Greek translations of the Old Testament.

- “The grotesques were, above all, ornamental painting. They are the site of transformations, metamorphoses, and hybrids. They are where the daytime world blends with the nocturnal, where real life merges with the dreamlike. Here, the boundaries between organic and mineral, the oneiric and reality, subtly dissolve. In the Renaissance, around the central, monumental biblical scenes, grotesques invade and take hold like creeping vegetation along the margins. They are the discreet yet subversive place where paganism survives,” Mattia Denisse and Arthur Dessine, Cata Log Cata Strofe, p. 308.