The screening programme Pelagic Archive explores the living archive that is the Atlantic world—a vast repository of stories, imaginaries, and histories that continuously reshape it. The selected moving-image works draw from collective memory and artistic research to trace fluid connections between histories of colonization, displacement, and ecological destruction. The Atlantic’s expanse reverberates in the fraught relationship between labour and the environment, between the histories of exploitation and survival archived in bodies, minds, landscapes, narratives, movements, and disruptions.

As Cabo Verdean artist César Schofield Cardoso argues, the ocean is “from colonial times to the present day an occupied, exploited, and toxic place.” Amid the global neoliberal order, with its greedy extraction, pollution, and trafficking, how can we reimagine this vast ocean as a space of dreams and livelihoods? The Atlantic is at once a wound and a horizon. It holds the memory of slavery, of routes mapped by violence, while also offering imaginaries of renewal. As Paul Gilroy argues in The Black Atlantic (1993), this ocean is a space of modernity itself—an irreducible field where the histories of Europe, Africa, and the Americas have become entangled in a system of circulation, translation, and rupture.

To think of the Atlantic as archive is to face the coloniality of the seas, where oceans and islands were cast as margins of empire, staging grounds for plantation economies and laboratories for extractive capitalism. This archive is not static but continues to be alive, layered with counter-narratives that resurface through art, ritual, and embodied practices. Pelagic Archive unfolds within this field of tension. The five films gathered create a constellation of perspectives that span Port-au-Prince, Ouidah, the Amazon, Cabo Verde, and Ceuta. Their geographies may be disparate, yet each insists that the ocean is not an empty connector of lands, but a shifting surface and depth where stories intersect. Like tides, the works resonate with one another, offering variations on shared questions: How is memory carried in bodies and gestures? How does extraction hollow out landscapes and societies? How might we reimagine the sea not as a frontier of dispossession but as a space of possibility?

Maksaens Denis’s Mes Rêves (2021) situates us in Haiti, where the aftershocks of revolution and its punishments continue to reverberate. The Black male body, choreographed in moments of vulnerability and defiance, traverses a dreamscape punctuated by images of protest and violence in Port-au-Prince. The film examines the body as archive—inscribed by the legacies of slavery and state repression, it resists erasure, becoming a site of imagination. In its oscillation between the intimate and the collective, Denis’s work reminds us that the Atlantic world is carried not only in ship logs or trade records, but in flesh, in sleep, in gestures of survival and resistance.

From this corporeal register, we shift to Ouidah in Benin, one of the epicentres of the transatlantic slave trade. In Tradição e imaginação (Tradition and imagination, 2019), Vanessa Fernandes works with Vodun priests and dancers to reactivate memory through movement. Along the “Slave Route” that led captives to the coast, the camera lingers on abandoned Portuguese buildings and heavy monuments, but it is in dance that history resurfaces with vitality. The sea, feared for its role in carrying millions into bondage, becomes a threshold for a choreography that honours loss and continuity. Fernandes also challenges the demonization of Vodun, often cast in colonial and Hollywood imaginaries as sinister. Instead, she frames it as a spiritual system of resilience, a cosmology that travelled across the Atlantic and shaped diasporic cultures. Her film expands the sense of the body as a vessel of memory into a collective, ritual practice that stretches across continents.

The ruins of Velho Airão in the Brazilian Amazon, captured in Janaina Wagner’s Cães Marinheiros (Sailor Dogs, 2020), shift the focus from slavery to the extractive logics that sustained colonial economies. Once a hub of the rubber boom, the town collapsed when extraction proved unsustainable, leaving behind legends of its people being “devoured by ants.” Wagner weaves these landscapes with Portuguese poet Herberto Hélder’s tale of the same name, creating a perspectivist inversion where words and images disassemble within a forest emptied of human life. Though geographically distant from the Atlantic coast, the Amazon’s rivers flow into it, binding local histories of exploitation to global circuits of demand. In Wagner’s lens, the Amazon becomes another Atlantic site: a hollowed territory, folded into the wider cycle of colonial boom and bust. The film underscores that the violence of the Atlantic was never confined to the coastline; it spread inland, shaping ecologies and towns, then leaving behind ruins and myths.

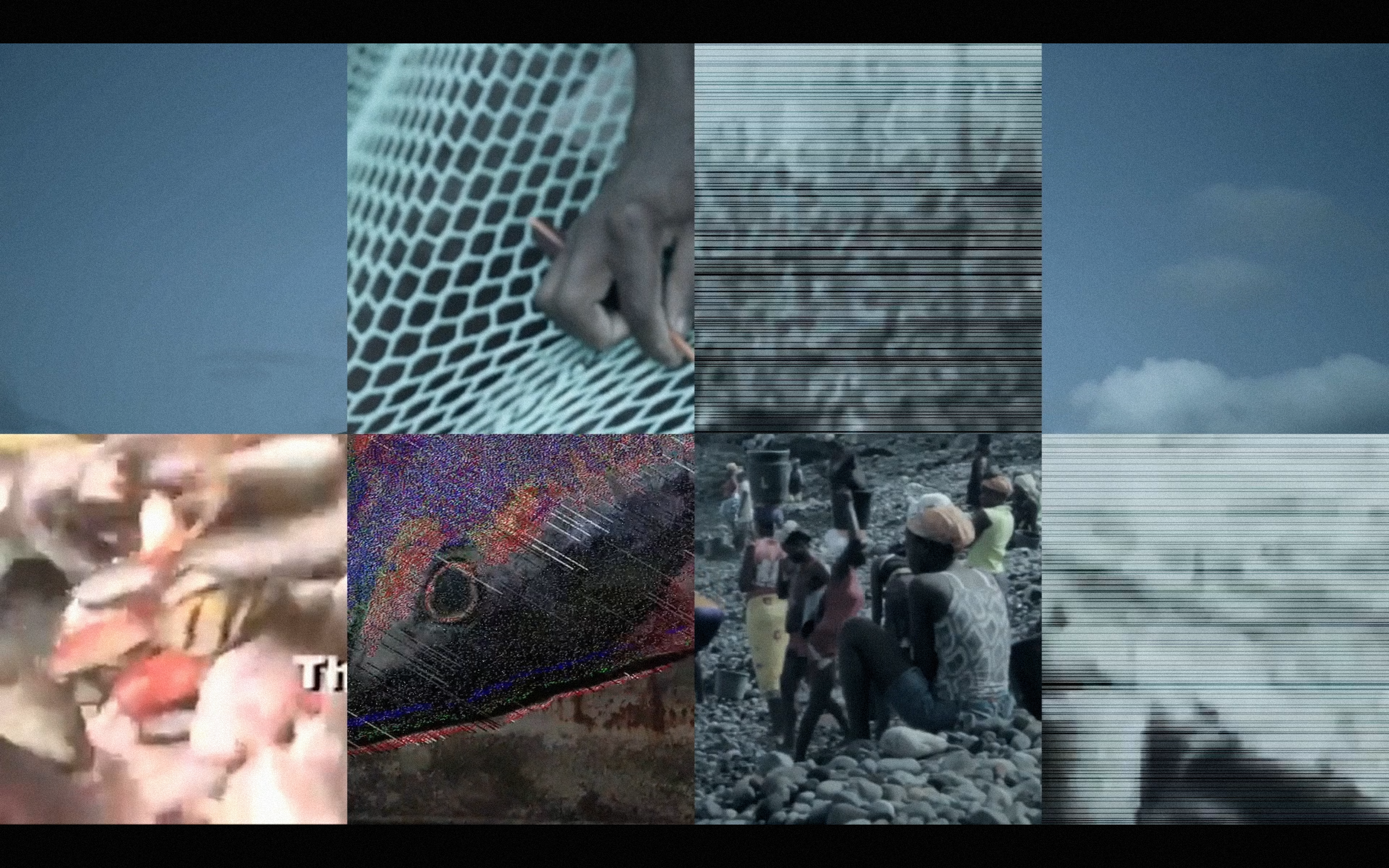

If Wagner reflects on what is lost in the wake of extraction, César Schofield Cardoso turns to what was foreclosed: the possibility of the ocean itself. In Blue Womb’s video work, There Are Many Fishing Vessels (2019), he probes Cabo Verde’s paradoxical relationship to the sea. Despite an ocean territory fourteen times larger than its landmass, the islands endured catastrophic famines under colonial regimes that failed to integrate the ocean into systems of sustenance. The sea was present as horizon but absent as resource, while policies of neglect condemned populations to hunger. Cardoso reimagines the Atlantic as womb, a space of potential futures rather than unhealed trauma, reframing the ocean not as absence but as a central ground for political ecology.

Finally, Randa Maroufi’s Bab Sebta (2019) situates us at the threshold of Europe, in the Spanish enclave of Ceuta on Moroccan soil. Here, the Atlantic archive appears not in ruins or memory but in the daily choreography of smuggling, where thousands carry bundles of goods across painted border lines. Filmed from above, the work transforms labour into ritual, repetition into endurance. Maroufi’s slow framing reveals the border as a stage, where the global logistics plays out on human backs.

Taken together, these works weave an Atlantic tapestry that resists closure. What emerges is what we might call a pelagic archive—not fixed in monuments or documents, but fluid, mobile, and embodied. Denis and Fernandes centre the body as vessel of memory; Wagner exposes the ruins of extractivism and exploitation; Cardoso reclaims the sea, reimagining it as womb of futures; Maroufi turns to the present border economy, showing how Atlantic circulations persist under new guises of legality and surveillance. Unlike a land-based archive that preserves, catalogues, and fixes, the pelagic archive drifts, resurfaces, recombines. It is kept alive in choreographed dances, in ruins overtaken by forest, in the silence of famine, in the hum of seismic waves, and in the lines of people crossing borders.

Pelagic Archive draws attention to the logistics of human and non-human systems in an interconnected, timeless world, navigating the spatial vastness of the Atlantic. It proposes to inhabit its currents, to listen to its resonances, to attend to its submerged voices. In the end, the Atlantic is a tide—receding, returning, reshaping—laden with echoes of the future and the persistence of past possibilities. Through the selected moving image works, we are invited to drift with it, to hold its traumas, and to potentiate its dreams.

—Ana Salazar Herrera, Pelagic Archive curator

Programme

September 5 to 14 — Maksaens Denis, My dreams (2021)

September 16 to 25 — Vanessa Fernandes, Tradição e Imaginação (2019)

September 26 to October 5 — Janaina Wagner, Cães Marinheiros (2020)

October 8 to 17 — César Schofield Cardoso, There Are Many Fishing Vessels (Blue Womb) (2023)

October 21 to 30 — Randa Maroufi, Bab Sebta (Ceuta’s Gate) (2019)

Image

César Schofield Cardoso, There Are Many Fishing Vessels (Blue Womb), 2023, Still

Proofreading

Marta Espiridião

Ana Salazar Herrera (born 1990) is an Ecuadorian and Portuguese curator of contemporary art, exploring nomadic, polylinguistic, and transcultural subjectivities. She co-founded the Museum for the Displaced (2019–ongoing), a platform addressing migration and cultural resistance. Currently a Curatorial Research Associate for Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale (DCAB) 2026, Riyadh, Ana was Co-curator, DCAB 2024; Interim Curator at Ludwig Forum Aachen (2022–23); and Assistant Curator at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (2016–20). She was part of the preselection committee for the 22nd Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, São Paulo (2023); Curator-in-Residence at Künstlerhaus Schloss Balmoral, Germany (2021–22); a mentee of Project Anywhere (2020–21); and a Shanghai Curators Lab Fellow (2018). She holds an MA in Curatorial Practice from the School of Visual Arts, New York, and a BA in Piano from Escola Superior de Música de Lisboa, Portugal. Her writing appears in art magazines, exhibition catalogues, and academic journals.