more-than-human — perspectives on technology and futurity presents six films that critically analyse from various perspectives not only the use of technology as a capitalist device and tool but also its impact on human existence. Reflecting on the complex relationship between these two realms, the films explore the interchangeability between the natural and the artificial, the robotic and the organic, and the tensions that arise from these processes.

Over the past two decades, the radical transformation and/or transcendence of the human condition through technology have given rise to profound ethical and philosophical enquiries. From a theoretical standpoint, this involves contemplating the advantages and risks associated with personal identity, emerging forms of otherness, equality and social justice, death and immortality, as well as religion and the meaning of life. From a practical perspective, artificial intelligence and human-machine hybridisation raise ethical concerns pertaining to physical, cognitive, and moral enhancement, as well as issues related to defence and security.

God, human, or more-than-human? A future of technological transcendence through biohacking, cognitive optimisation, and other biomedical technologies aims at overcoming the physical dimension—the expansion and preservation of consciousness into a new biological-artificial body. Technology operates as a promise of omnipresence, omnipotence, and omniscience: in other words, immortality. From science to cosmology, from supernatural and artificial intelligence to science fiction, incorporating critical approaches that go beyond normativity, more-than-human implies a reassessment of our relationship with life. Likewise, it promotes networks of ethics and responsibility, collective forms of knowledge production, and other modes of interpretation and understanding that transcend the boundaries between self and other, human and non-human, organic and technological. In the same vein, it entails a sharing of common concerns, motivations, and challenges, despite any critical or methodological differences that may arise. A future of ecocentric consciousness calls for the end of anthropocentrism, rethinks humanity beyond its supposed centrality, and integrates more-than-human perspectives that recognise an environmentally sustainable and ethically conscious future, incorporating ethical, aesthetic, political, and social issues inherent to the contemporary condition.

Brave New World1 —technological advancements depicted in certain dystopian and apocalyptic scenarios are linked to political, economic, and social instability. Contemporary technological development seems to embody forms of power and authoritarianism that challenge basic foundations of social organisation, which, like the structuring of interpersonal relationships, is undergoing transformation. We live in a scenario where digital communication and social media shape our existence and offer an opaque mirror of bodyless narcissistic egos. The extent of the manipulation of our data is incalculable, but the production of capital depends on this exchange and circulation of information operating through digital platforms grounded in purely extractive and capitalist values: “Capitalism is a translation machine for producing capital from all kinds of livelihoods, human and not human.”2 Technology can simultaneously represent the problem and the solution: by considering more-than-human plural narratives, we can create a shared reality, imagining the future now.

– Celina Brás, artistic direction

Synopsis

AnaMary Bilbao, Prelude, 2023, 16mm transferred to UHD video, 7’10’’, colour, sound

“La mort” — death — only anticipates what is yet to come. The gesture of the hand-written “La mort” reveals an energy and mobility otherwise absent in the work’s puppet-like figures, if not for the camera’s own movement over the images themselves. The puppets’ uncanny anthropomorphism signals something that resembles, yet does not reproduce, a human or animal figure. Standing in, however, for their indexes, these symbols evoke a life unlike the one we know. In his canonical work Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes reminds us how cinema, unlike photography, which fastens down figures “like [preserved] butterflies,” enables beings to continue living (56–57). The cinematographic present is alive, carrying its referent without being tied to it. Bilbao’s diabolic lanternflies, or lanternfly devils, dance in stop motion, refusing to be pinned down like a dried, dead butterfly. In their motionless movement, Bilbao’s lanternfly flutters, confronting the humanity of the anthropomorphic yet inert clown-like puppet. AnaMary Bilbao’s oeuvre continuously questions notions of origin and conclusion. “All my processes revolve around the beginning and the end of images,” explains the artist in conversation. (…) Here, for the first time, Bilbao is not in direct touch with the image’s materiality; rather, she engages with virtual representations of artificially engineered images. As the artist explains, “DALL·E never ends; it always offers more and more variations of the same image. The image, then, is never ready; it never finds its conclusion. It is transformed by new information while simultaneously producing new data. The algorithm has no end in sight.”

— Alejandra Rosenberg

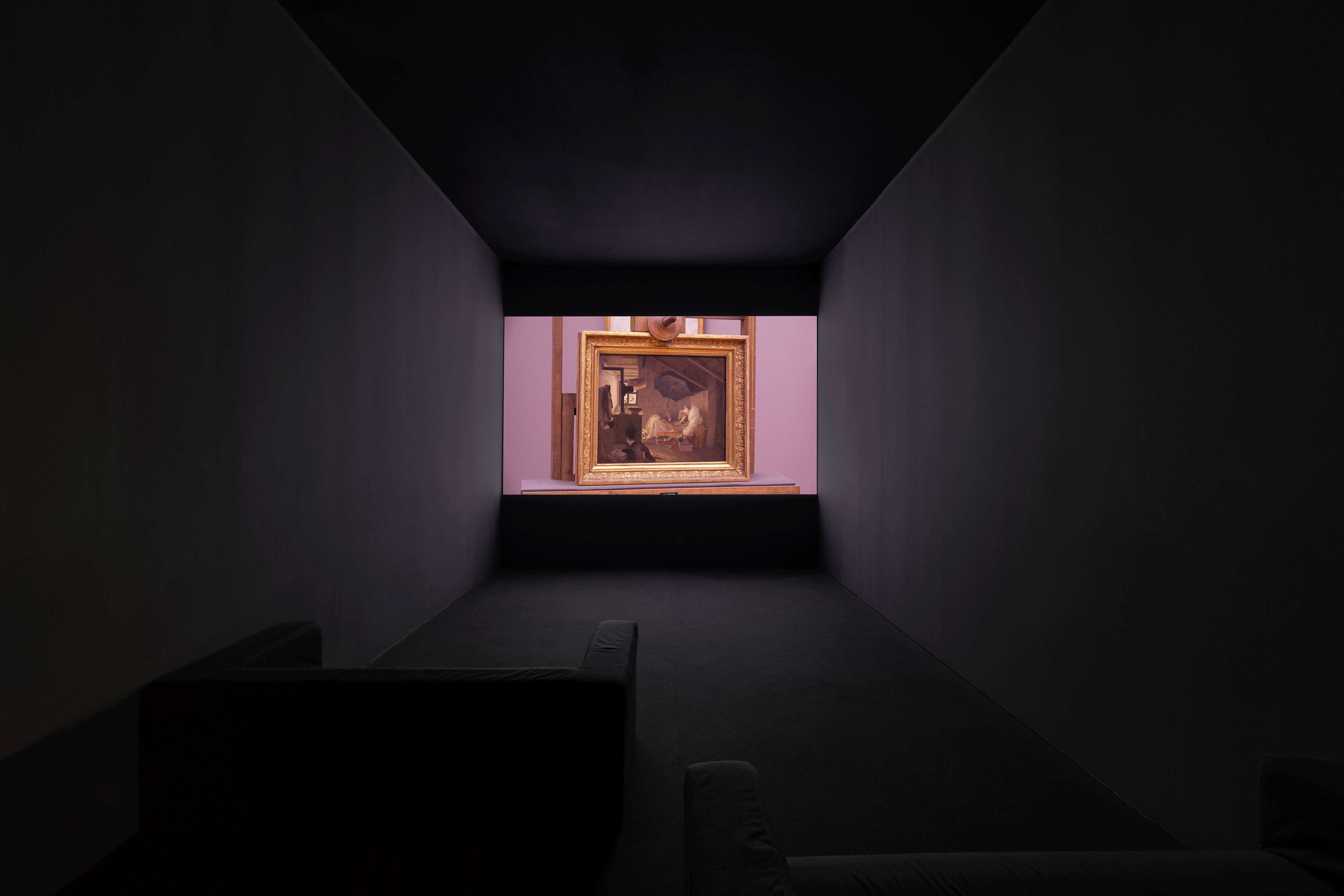

Igor Jesus, Ventríloquo, 2024, (3x) Silver gelatin print, metal, full HD projection, and speakers. Generative image created through receiving and interpreting radio frequencies

A parrot captured through a lens distorted by hand-polishing techniques reveals the image guiding the construction of antennas for tuning into amateur radio conversations. Ventríloquo delves into the idea of language asserting dominance over the image, using the parrot’s vocabulary as commands to intercept and interfere with the radio chatter. Simultaneously, it manipulates the beams of light from the projectors, crafting luminous displays that influence the image and empower the parrot to deliver a sculptural cinematic experience.

Pedro Barateiro, Love Song, 23-2024, 40′, HD, colour, sound

A film on growing up with technology and the bonds between human and non-human agents, Love Song is both autobiography and autofiction. The film deals with subjectivity and the realization of the changes that transform the individual and the collective. Love Song departs from my teenage years and an awareness of the body—of the so-called self— as a space where the interior and exterior are confronted, and the layers they engender. The film takes the example of my parents, who dated mostly by correspondence, and the romanticized aspects of their interactions set in late 1960’s fascist Portugal, between immigration (mother) and colonial war (father).

Love Song rejects any form of identification. It started as an audio piece, a soundtrack for a film that is still being made and that will grow into something else. It is about the conventions of narrative and how they’ve been manipulated by capital, connecting Romanticism (the movement in the 19th century) and Capitalism (the modern use of the word since the 19th century) and the binary systems fostered by biology and religion, to question forms of production and the changes they generated in Europe and in the West. Love Song tries to address the uses and misuses of the word “love”, and how it is appropriated in neoliberal western societies under an imminent collapse of social and natural systems.

Artistic Direction

Celina Brás

Hours

Terça a Domingo

10h–13h / 14h–18h

Location

Galeria Avenida da Índia

Organization

Contemporânea

Support

DGArtes

Date

18.02–24.03.2024

Performance Gisela Casimiro

12.01.2024 [18:30]

Artists

AnaMary Bilbao

Igor Jesus

Pedro Barateiro

PT-EN translation and proofreading of EN synopses

Diogo Montenegro

Photos

Bruno Lopes

Acknowledgements

MAC/CCB

Entrance

Room Sheet

Children's Room Sheet

Galerias Municipais de Lisboa/EGEAC

- Admirável Mundo Novo (Brave New World), Aldous Huxley, 1932.

- The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, 2015.