Mixture and Metamorphosis

1.

Philosopher Emanuele Coccia writes that life is a metamorphic mixture. For him, the world is an accumulation of folds, co-mingled grooves that allow for discrete passages between their phases. Thus, the core of existence is constant transformation, or the obstinate perforation of this architecture of fringes: the crossing, the encounter, the symbiosis, and the continuous reincarnation of forms, themselves fragmentary, into fickle facts. We live, however, as if none of this were the case. In order to function every day, we feign more or less autonomy, insularity, and obstinacy; we ignore our paraconsistency; we cover the volcano of difference with a thin layer of cotton, praying to some unnamed cosmic law or abstract force that should press open reality and guarantee the eternity of things.

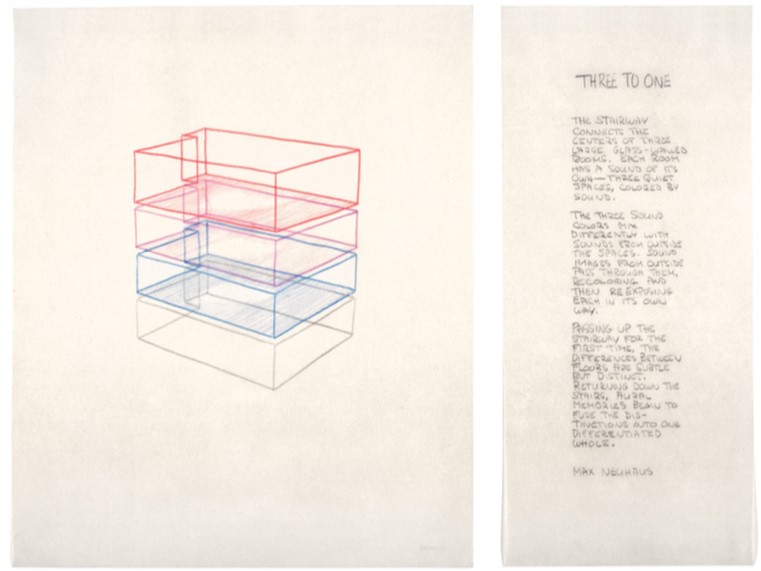

Vision—which Michel Serres says dominates the other senses in Western culture—has also always favored metastability over process, concrete over concrescence. The eye provides the perfect structure for the impression of an object’s permanence: contour, color, opacity, depth, solidity. Everything that is seen is rooted in a hard topology at the end and bottom of the imaginary. Sound, on the other hand, is phantasmatic. It modulates presence and absence without respecting the boundaries between bodies. While visuality separates and delimits, aurality merges, dissolves, submerges. In listening we are invited to inhabit the transitory: to come and go, leaving only floating trails of attraction instead of the straight demarcations of an ontological soccer pitch.

This is why sound is an ideal medium for the constitution of diasporic cultures. Music is open to the associative mixture required by wandering, and dispenses with the totalitarianism of filiation, Édouard Glissant suggests. Migration and mestizaje, which are nothing more than exemplary types of metamorphosis, find their counterpart in sound. Metamorphosis is sharpened by the eardrums, which archive the ephemeral and ephemeralize the archive, making us all transmission tools for broad circuits of undoing and remaking—even civilizational ones, as in the case of diasporas. The musical instrument is a technology of cross-pollination, through which entire populations are translated into gestures that are then translated into vertigoes, or precipitations to the other.

The compositions here presented, by Arto Lindsay, Wendy Eisenberg, Ben Vida, and Julia Santoli, either start from mixture and metamorphosis (be it national, sexual, formal, methodological) or find it at the end of their production (through distancing, disarrangement, contradiction, superposition). Here is a constellation of noises that underline, rather than sublimate, the tendency of sound to fade away. Sometimes compressed, sometimes improvised, sometimes detuned, sometimes mixed to the point of strangeness, they all evoke the radical and inevitable changes that both artists and their art need to go through.

2.

Metamorphosis has perhaps been exhaustively symbolized by the butterfly, which in the condensation of the larva into a pupa and the subsequent shedding of the chrysalis rehearses a circus-like provocation of the logical principle of identity. Drained by kitsch, covered in a thick layer of clichés, turned into wallpapers in children’s bedrooms or coccyx tattoos for dentist’s secretaries, the butterfly has gradually lost its ability to sustain such allegorical aura. But it’s no wonder that the Greeks called the soul psyche, which also means “butterfly.” No wonder Nabokov, an inveterate collector of butterflies, developed the vocation of writing only to describe them from an early age. No wonder Warburg, imprisoned in the Bellevue Sanatorium, formed a hallucinatory alliance with the butterflies that entered his room. As a materialization of metamorphosis, the butterfly begs for a ritual interpretation.

First of all, of course, the butterfly’s shimmering appearance, like a flame trapped in a wax disk, invites us to an explosive hope in the world’s—almost pompous—creative capacity. The biological emerges from the mineral, the wind from a slightly varied vibration, and everything that looks like calculated causality has actually fermented and unfolded from the womb of a single animation. Secondly, the muteness of the butterfly, the lack of any communication, which also seems to conspire for secret purposes, mutations that escape us. A creature, says Roger Caillois, is the surface of a hidden movement towards its surroundings, the neutral consequence of a generic, universal erosion of all things against all others. And thirdly, the butterfly’s bewildering mode of flight, the lack of criteria in its movement, completely unpredictable and even frightening as it flits from flower to flower. The vagabond anarchy of the butterfly.

Those born in certain cities soon learn to read the world in the form of transit. Traffic laws as laws of the general movement of life. Uninterrupted ups and downs, or life as the careful regulation of a flow of analogical events. Consider the Universal Metamorphic Machine. Those traffic laws also applied to butterflies, and vice versa. Not just to their flocks and landings, but to the broad design of their circadian cycles, and then their evolutionary cycles, intertwined, as they are, with our own. Even more so because, up close, nothing stands still: even the oldest mountain is nothing more than a series of knots and twists and shards and stings stretching out from the base of the floor to achieve relative homogeneity. Rather than the permanence of the object, it always seems to be a very slow frequency, or an uncapturable rhythm, or a soft, gray vector, call it what you want.

One day you're in the back seat of the car heading to the countryside and the car passes through a cloud of orange insects, cutting one by one as they sweep over the windshield, and your grandma grunts insecurely and her fingers turn white from clenching to the wheel. The car window is filled with a salad of multicolored corpses, translucent wings like sheets of shredded cellophane. The other day, it’s the video—possibly fake, augmented by artificial intelligence—of hundreds of supersaturated cocoons blooming in a domino effect for the pleasure of a dozen tourists, and the roads no longer have so many bugs, extinguished as they were by the glory of production, and grandma no longer drives, and the countryside is not even the space of that familiar security but a portal for egoic pulses loosely assembled by the algorithmic metabolism into a caudillist monster.

The world is gradually transformed on all of its scales, we notice a tentacular drag, even if we can’t see it with the naked eye. When I search my memory for the sound of dead butterflies, though, I can hear a fine-tuned orchestra of metamorphosis. At the heart of everything is a life-sized vortex.

Rômulo Moraes is a Brazilian writer, sound artist, and researcher. He is a PhD candidate in Ethnomusicology at the CUNY Graduate Center with a Fulbright/CAPES scholarship and holds a Master’s degree in Culture and Communication from UFRJ. He is the author of “A fauna e a espuma” [7letras, 2023] and “Casulos” [Kotter, 2019]. He teaches at Bard College, Brooklyn College, Queens College, and the New Centre for Research & Practice. His essays and reviews have been published in journals such as e-flux, The Wire, The Brooklyn Rail, Aquarium Drunkard, and The Whitney Review, among others. His current interests include the phenomenologies of imagination, the entanglement of pop and experimental music, the cosmopoetics of prospecting, and the concept of “vibe” as an aesthetic category.

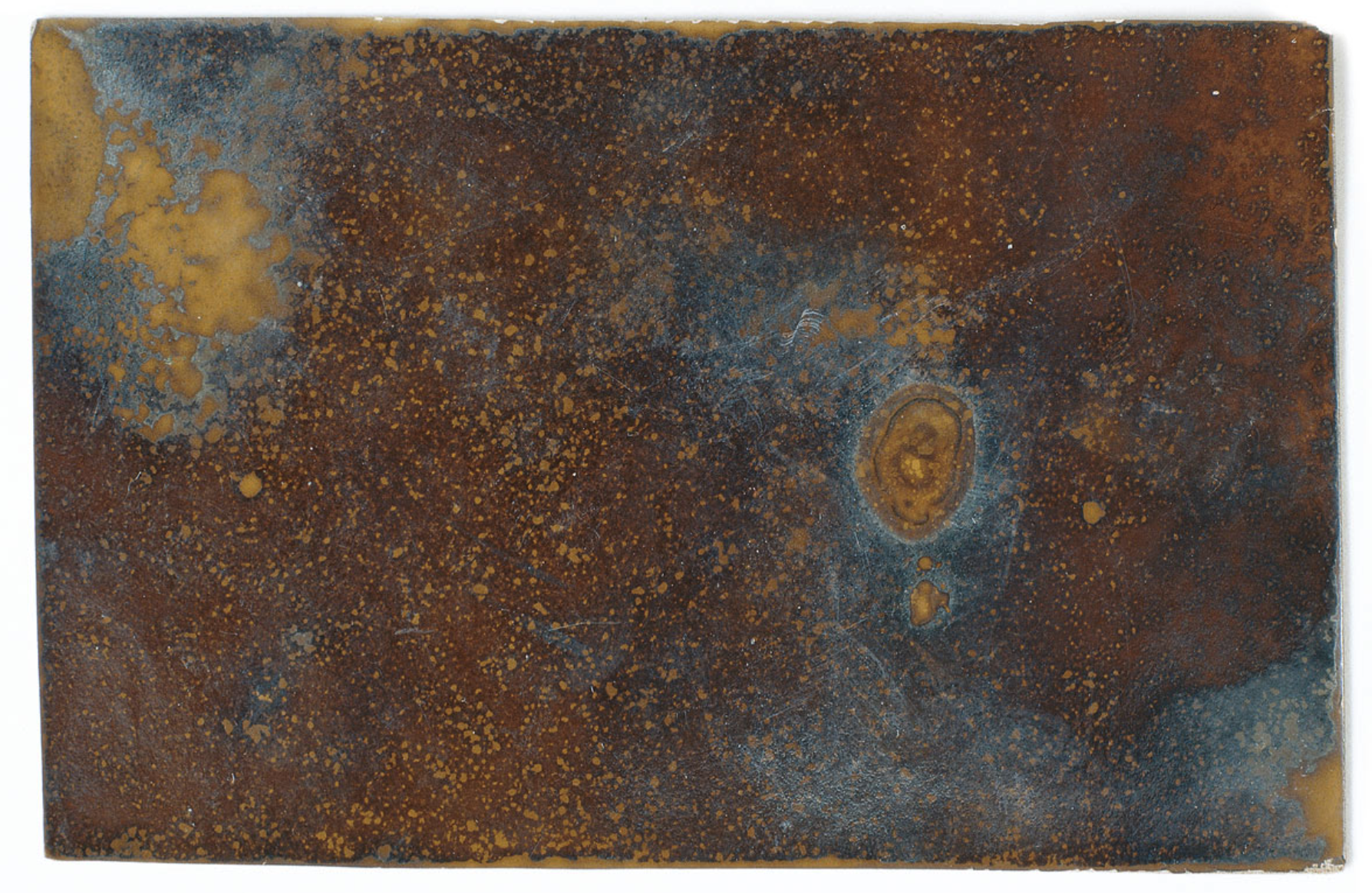

Cover Image: A celestograph by August Strindberg, 1894.