On the night of 13 March this year, Independence Cinema opened at the Batalha Centro de Cinema. Curated by researcher, activist, and cultural critic Kitty Furtado, the exhibition revisits the liberation struggles of the African countries colonised by Portugal through what she describes as guerrilla, counter-colonial, and independence cinema. Focusing on films produced in Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and Mozambique, the show offers a concise overview of the vital role that moving images played not only as tools of struggle, resistance, and documentation, but also in the "international dissemination of emancipatory messages."

As part of a project that views the Atlantic as a contested territory of imaginaries, we sat down with the curator for this edition of Ocean Writings—an opportunity to understand how independence cinema continues to bring together geographies, liberation processes, historical timeframes, memories, and political discourse.

Paula Ferreira: I’d like to start from the beginning. How did the idea for the exhibition first come about? And how did the research process develop?

Kitty Furtado: The exhibition is the result of a synthesis of earlier research, also drawing on the work of other researcher colleagues. It came about through an invitation from Batalha Centro de Cinema to curate a show on cinema in the former colonies, marking fifty years of independence. We didn’t want it to focus solely on post-independence cinema, but rather to trace a broader continuity, a cycle, including what I call counter-colonial and guerrilla cinema—that is, films made during the liberation struggles. In all three phases, cinema played a central role, first by helping to spread emancipatory messages and then by supporting the process of nation-building.

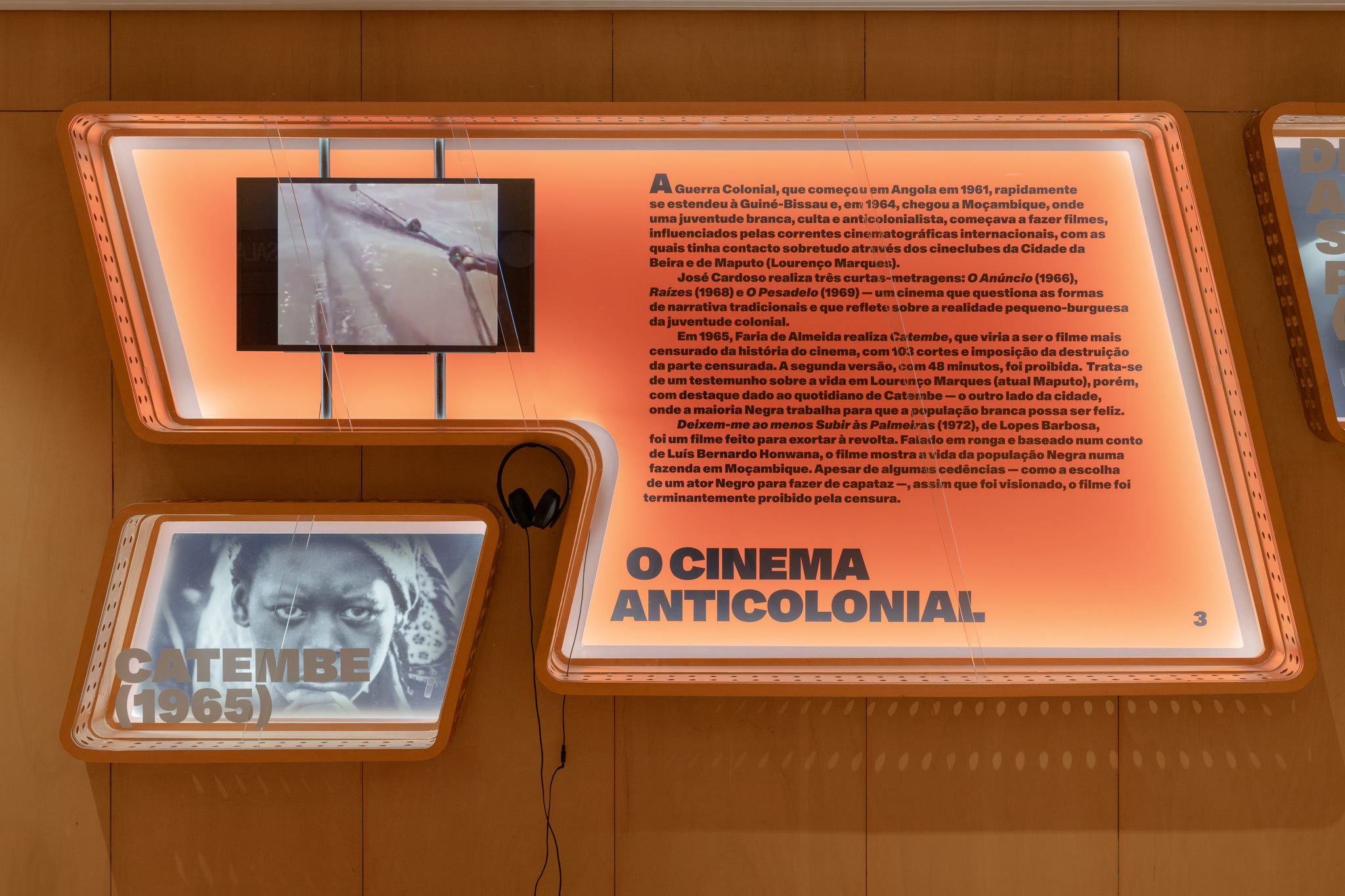

PF: Certain circumstances come to light when we try to “recover” the histories behind many of the films made during the independence struggles. Take Catembe, which was almost entirely censored, ultimately distorting its meaning; or Deixe-me ao Menos Subir às Palmeiras…, shot under near-clandestine conditions—both shaped by the very circumstances in which they were produced. In the process of researching and “retrieving” these and other films, did you make use of any resources from, for example, the Cinemateca Portuguesa or other archives that hold the memory of these works? And what do these "small" behind-the-scenes stories of production and circulation tell us?

KF: On the Cinemateca and other archives, I should clarify something from my first answer: I wasn’t the one who did that archival work. In the case of the two films you mention, the one who researched them—and even uncovered Deixe-me ao Menos Subir às Palmeiras…, which had been completely forgotten and lost in the Cinemateca's archives—was Maria do Carmo Piçarra, back in 2015. When I travelled to Mozambique in 2016 to work on my PhD (focusing on contemporary Mozambican cinema), I already had that information, and managed to track down the filmmaker, who was still alive. I did several long interviews with Joaquim Lopes Barbosa, who told me he didn't know a copy of the film still existed.

At the time, the film’s rediscovery was still recent, so it was incredibly moving to hear him recount those details—which, of course, are hugely important. I learned so much about how the film was made, about the footage he captured while working at Somar Filmes, producing cinema newsreels, short audiovisual segments with news shown before the main feature in cinemas, in the days before television. When he went out to shoot news items, he also filmed things he wasn’t supposed to, like life on the machambas (plantations). So the footage we see in the film (Black people working, queues for food, and so on) arguably has the feel of cinéma vérité, which was very much in vogue at the time. In essence, these were images he “stole”—in big quotation marks—from his boss, Courinha Ramos, who was aligned with the colonial regime and still agreed to back Deixem-me ao Menos Subir às Palmeiras…, unaware of its real intentions. A lot of people were living in a kind of denial, convinced that the war would never reach the capital, never reach them. Only when the film was shown to the PIDE did Courinha Ramos realise what Lopes Barbosa had done—and that was when he was fired, left with no job, no film, nothing.1

[Lopes Barbosa said] it was an incredibly harsh blow, because he’d thought he could circumvent the censorship system by making a few concessions. For example, the character of the foreman was portrayed by a Black actor, whereas in Luís Bernardo Honwana’s original short story he’s a white Portuguese man. The plantation owner was portrayed as South African, though he was Portuguese in the original. Lopes Barbosa thought these small changes would be enough to fool the censors, but it was quite clear the film had been made to inspire revolt against the colonial regime. It was also very clearly made for an African audience, since the characters speak in Ronga, a local language, and not Portuguese, like in the short story…

PF: That’s a conscious choice about who the films were speaking to, right? I’m also wondering how we might look at that gesture today. Would making films in the coloniser’s language be a way of internationalising the struggle for independence?

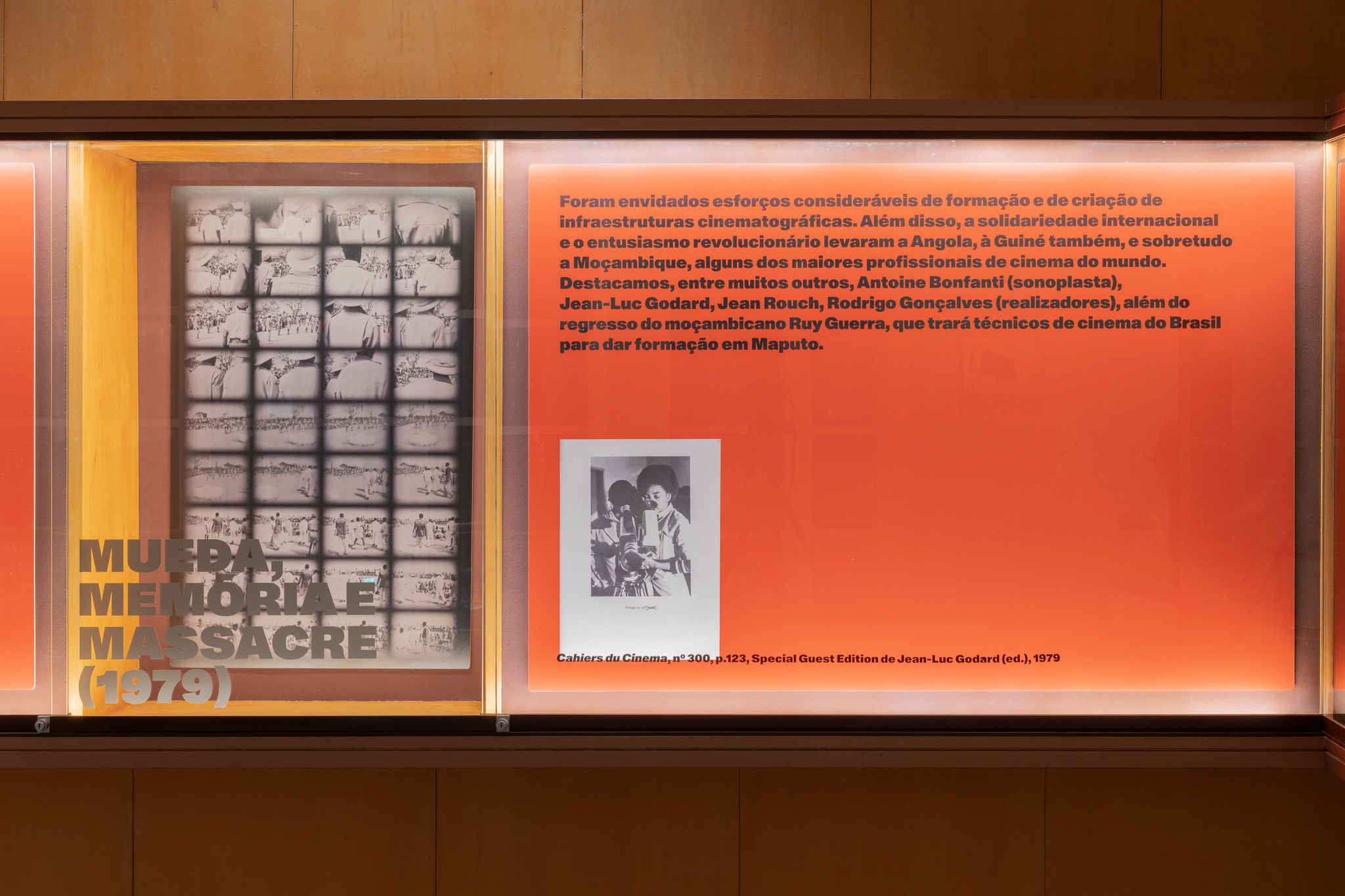

KF: The films I refer to as “guerrilla cinema” were made alongside the armed struggle: out in the bush, among the guerrilla fighters. Those films were absolutely made to spread a message of emancipation, to win allies—and they were only possible thanks to the efforts of many international allies. Almost all of them were made by foreign directors, as the guerrilla movements had yet to include filmmakers among their ranks. Radio was easier, photography too, but cinema required economic and technical means. And yes, the aim was very much to show the struggle to people in the United States, Europe, the Soviet Union… basically, to any progressive left-wing audience willing to circulate them.

But what I now call “counter-colonial cinema” isn’t the same as guerrilla cinema: these were films made by a younger generation of settler-colonial filmmakers, like Lopes Barbosa himself, who had moved to Africa as an adult. He, and many like him, wanted to be proper filmmakers, to make work that was politically relevant but also meaningful in artistic and cinematic terms. They were young people making these films; and if you’d asked them, they’d have said they wanted to be like Jean-Luc Godard, or any of the great filmmakers of the time. And perhaps they would have been if it weren’t for censorship. Take Faria de Almeida, who directed Catembe: he studied and won awards in Europe… They were heavily influenced by French and European cinema. But there’s something interesting here, I think: if we consider, for instance, the Nouvelle Vague, those filmmakers made it through the entire Algerian War without ever addressing it in a single film, just as the Portuguese Cinema Novo never made films about the colonial war.

PF: That’s a really important point, and it brings up a question I found myself asking while preparing for this interview. I kept thinking about what happened to films like Deixe-me ao Menos Subir às Palmeiras…, which even after the 25th of April remained “lost” or “forgotten.” What does that tell us about Portugal's difficulty in confronting the colonial reality and its images?

KF: Well… it’s the same as always, across the board. The fact that the film lay forgotten in the Cinemateca after the 25th of April says it all, doesn’t it? In truth, Portugal has never known how to deal with its colonial past, and cinema is no exception. Starting in the 1990s, for the first time, a generation of filmmakers did begin to look at that past, to touch that wound. These were people who had been children or teenagers during the war, and they felt a need to open that chest, to look at their own childhoods essentially. But they often did so through the lens of loss, through family stories. Rarely were these films made by women; and when they were, they tended to centre on the sense of waiting, on the feeling of being trapped. In those films, you don’t really see the war—I’m thinking of Margarida Cardoso's Costa dos Murmúrios, or Teresa Villaverde's A Idade Maior—but rather the suffering of those whose lives depended upon it. What was still missing, I think, was the relationship with the other, a reflection on the violence that had been inflicted. These were films about the self, for the self… It’s a difficult, complex subject.

The most compelling work on colonial memory today, I believe, is being done by African and Afro-descendant people. That’s the cinema that’s offering a different gaze on the past, that’s seeking out the stories that were rendered invisible—and doing so with great courage, often with very few resources. I believe those films are making an important contribution to how we understand ourselves. But I want to say something else too: I don’t believe in exceptionalism. I don’t think the Portuguese are exceptionally gentle, exceptionally open to racial mixing—all those Lusotropicalist myths. But I also don’t think they’re uniquely silent or silencing, incapable of reflection. In reality, every European nation has crafted narratives that are convenient to itself.

PF: That leads me to the question of reparations, and what I think is often a misreading of what’s at stake when the subject is brought up. Notwithstanding the importance of restituting stolen or looted objects, it’s only a tiny part of what genuine reparation might look like. There are so many other areas that need repair, some more tangible than others. One of them is the reparation of narrative and memory, which is a recurring theme in your work. Could you say a few words about that, or about other forms of reparation you feel should be part of this conversation?

KF: Well, that’s a big question… Not an easy one to put into words. I think we need to begin with processes of self-repair. To name just one reference, I’m thinking of what the writer Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida says: these processes of self-repair are vital in Black and Afro-descendant communities, because what was taken from us was interiority—and that reparation or restoration, really, is part of our inheritance. Why do we have to do it ourselves? Because there is no one—no institution, no court—that will acknowledge the crime against humanity that colonialism was, the expropriation of our interiority. But if we also bring Fanon into this, we might say the coloniser, too, was a victim of that violence, right? The world is shattered in every direction. White communities also need to self-repair—perhaps by shattering the very notion of whiteness. Because if not, the same violences, the same abyssal hierarchies, the same constructions of race, gender, and class—the very structures that have brought us to a world without a future—will keep repeating themselves.

It’s clear this [world] isn’t sustainable: its models of development aren’t sustainable; its ways of relating across peoples aren’t sustainable. So yes, those processes of self-repair are really important. Which brings us to the million-dollar question: is reparation even possible? Denise Ferreira da Silva says the debt is unpayable, right? I agree there’s no way to repair what History owes to millions—to the victims of colonial violence and its ongoing logics. So what’s left for us is to imagine the world that might come after this one: a world not governed by the thinking born of European Enlightenment, a world beyond modernity.

Our struggle is twofold. On the one hand, we have the work of imagining that future world; on the other, we have to keep repairing the one we still live in. That might seem contradictory, but the truth is we have to arrive whole—and alive—at this future we've imagined.

PF: That’s a truly beautiful vision—the idea of self-repair, which I also believe is essential to any project of creating a new world. Now, on a more immediate level, what can we say about reparation from a material standpoint, thinking of cinema in physical terms, film restoration, and so on?

KF: I think the same logic applies to films and to archives. We need to approach archives differently because they’re ours. They belong to us. But they always seem to have a kind of border: not everyone can access them. And then there are those that have been damaged or neglected because of underfunding or lack of resources. So whether it’s through excessive gatekeeping and elitism or through neglect, the archives end up not being ours after all.

PF: Ultimately, the way we deal with all this comes down to the politics of collective memory. What role can academic research play in that field?

KF: Academic research can only really do that: research. It can show just how invisible some parts of History and memory have become. It can say: “This part of history has never been told, this perspective is never addressed, this archive isn’t accessible…” Beyond that, in my view, research should be careful not to speak only to itself, but to bring its questions and findings into the public sphere… And just to be clear, I’m not saying rigorous scientific discourse—the kind only specialists are likely to grasp—shouldn’t exist. I’m just saying that, in parallel, we also need to make an effort to speak in ways people can actually understand. We need to speak to and engage with grassroots movements, because they’re the ones who can push for different public policies. So that’s what academia should be doing: staying engaged with civil society.

PF: I’d like to go back a bit and pick up on a word you used earlier: Lusotropicalism—the way that concept helped shape an imaginary of peaceful coexistence, tolerance, even racial equality. How did the propaganda films of the Estado Novo operate as ideological weapons to reinforce that Lusotropicalist imaginary? And how did other kinds of cinema begin to unravel that agenda and reveal the racial segregation that existed in the former colonies?

KF: When Gilberto Freyre published Casa Grande e Senzala in 1933, the book was actually banned in Portugal—at the time, a eugenics-driven project was underway in the country. But after the Second World War, in response to international pressure, the Portuguese government decided to adopt the theory of Lusotropicalism, which had already been well received by certain Portuguese intellectuals, and to turn it into a kind of national ideology. There had already been something of a proto-Lusotropicalist discourse brewing, and the story of how that discourse was constructed is really quite interesting. In any case, the truth is by the 1950s and 60s, everyone in Portugal had been repeatedly told on the radio, at school, in church, and even at the cinema that the Portuguese were naturally inclined to mix with other peoples, that Portuguese colonialism was benevolent, that the Portuguese weren’t racist—all those Lusotropicalist myths that Freyre helped reinforce.

What is the Lusotropical man, after all? He’s precisely the Portuguese man who arrives in the tropics and “mixes” with the local population, giving rise to a “new race.” Gilberto Freyre was invited by Salazar to visit Portugal, and even travelled to the former colonies to write about them. But when he got there, he couldn’t see the Brazil he had written about, so he tried to reshape reality to suit his theory. It wasn’t the theory that needed revising; it was reality that was wrong. [chuckles]

As for cinema, the counter-colonial films were made by an educated youth who, in various ways and for different reasons, had access to what was being done in philosophy and politics, particularly in France. They were a Francophone generation, influenced by the progressive currents gaining traction in Europe. They began to realise that what the Portuguese government was promoting simply didn’t align with the world around them. Furthermore, nourished by film clubs and the cinema being made at the time in Europe, the Soviet Union, Brazil, the United States, and elsewhere, they wanted to make films that mattered politically, yes, but also artistically. So it was from that "mix"—a socially dramatic situation under a dictatorship—that counter-colonial and guerrilla cinema emerged, both of them pushing back against Portuguese colonial propaganda.

And of course, there are circumstantial differences between the two. Guerrilla cinema was “bush cinema,” made alongside the fighters. It was political, and aimed at winning support for the liberation struggles and show the world what FRELIMO, PAIGC, MPLA were, among others—their liberated zones, their schools, their hospitals… It was documentary cinema, not fiction. Counter-colonial cinema, on the other hand, was urban, made by young settler-colonial filmmakers who had attended film clubs, studied at European film schools, and returned to make films. Whilst there may be overlaps between the two genres, at the end of the day, we name things so that we can think about them, right?

A third phase of Independence Cinema focuses on the films made after independence. As I write in the exhibition text, this was a cinema strongly rooted in documentary, and one that offered an African perspective on the history of colonisation and the independence struggle, drawing on that memory as a foundation for constructing national identity. Many of the peoples in these “new” countries had lived in isolation from one another, often unaware of the full scale and ethnic diversity of their country—whose borders had been imposed by European powers in the first place. So cinema became a vehicle for mutual (re)discovery, and also for building national unity. In this sense, despite their differences, post-independence film projects should be understood as part of broader strategies to construct national identities and, at the same time, consolidate the political programmes that brought them into being.

O Cinema das Independências. Exhibition views at Batalha Centro de Cinema, Porto, 2025. Photos: Dinis Santos. Courtesy Batalha Centro de Cinema.

Tradução PT-EN: Diogo Montenegro

- This account is told in the first person in one of the interviews featured in the book Conversas Sobre Cinema em Moçambique, published in 2022 by Ana Cristina Pereira (Kitty Furtado) and Rosa Cabecinhas. This volume is dedicated to the memory of Lopes Barbosa.